Although traditional wisdom is that the four flush is not worth trying to improve, here Prof. Ankeny considers the case where betting was opened by the last player to have the opportunity - the player on the immediate right of the dealer. In this case all players know that none of those before him had a hand which was worth opening on. This in turn makes a lowly pair of jacks with crappy side cards worth trying to improve by opening, so that may be the case.

Game theory claims that for every situation there is a best and worst possible play, something we can probably all relate to from certain Tic-Tac-Toe situations. Prof. Ankeny then uses it to show us that in the above case, the four-flush can be made to be a winner; see Figure 1/Table 3.1.

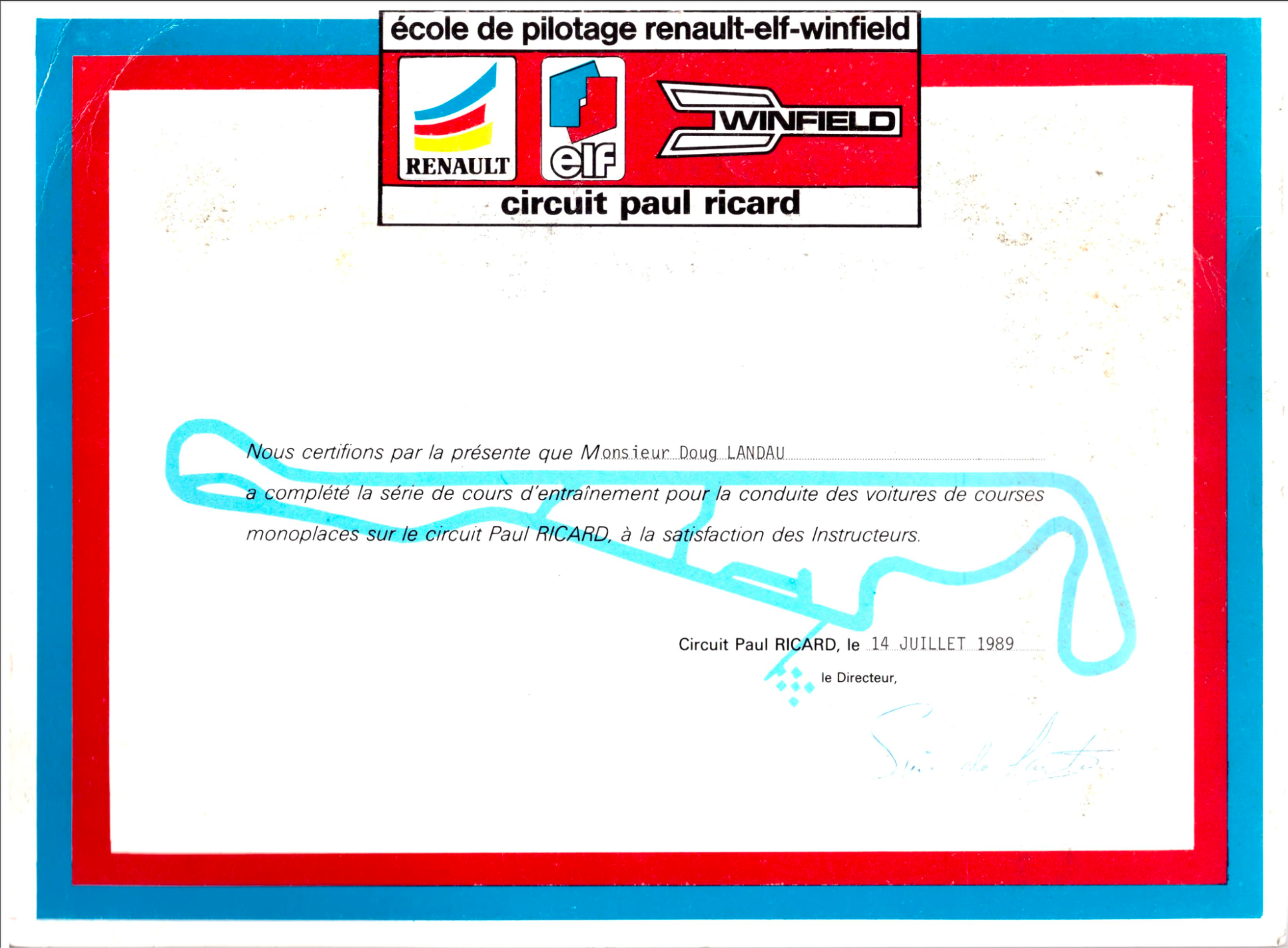

Figure 1. (Table 3.1)

The optimal strategy in player B’s four-flush situation is in offensive strategy, in which B adopts a bluff ratio of 1:2 - one bluff bet for every two strength bets. If B does this, A can do nothing to prevent him from winning an average profit of $3.60 per hand. Conversely, if A adopts the optimal calling ratio of 1:1, he prevents B from winning any more than $3.60 per hand.

The Theory of Slow Turns applies only to cars whose designs subscribe to the Theory of Slow Turns. In other words:

- In theory, the Theory of Slow Turns applies only to cars which are points or bricks or otherwise enjoy a perfect distribution of mass which places their CG at their centroid, or directly below it.

- In practice, the Theory of Slow Turns applies only to mid-engine cars with front wheel steering.

Do not try this in your Porsche.

There are two pieces of background knowledge the reader must have at this point: the definition of slow turns, and the braking and turning force fundamentals.

Fast turn: A turn for which you as the driver would not lift. A clean example of a fast turn can be seen at 1:27 here Hakkinen Battles Schumacher At Spa | 2000 Belgian Grand Prix

Medium turn: One for which you would lift and perhaps brake lightly to moderately

Slow turn: One for which you would brake hard and deep into; perhaps 1⁄3 - 1⁄2 way. A clean example of a slow turn can be seen at 0:24 here fernando alonso onboard pole lap at magny cours 2005

Apex: A.K.A. the clipping point, the middle of or tightest point in a turn

This theory accepts as correct the assertions regarding the forces acting upon the car made in “The Technique of Motor Racing” by Piero Taruffi[1].

Figure 1. Forces acting on a car in a turn.

Figure 1 shows the forces. The braking force is towards the rear of the car; we are more interested in its absolute value. Taruffi claims that when the magnitude of the vector sum of the braking and turning force vectors exceeds the available traction, the car will lose adhesion and leave the road in the direction of the vector sum.

This diagram presently has this error: the car is shown in the middle of the turn, when the brakes should be fully off, but the braking force vector is not drawn with zero length.

1(a) Postulate 1

At the end of the straightaway the driver must be braking as hard as is possible without locking the wheels. In other words using, by braking, as much of the available traction as is possible without using it all.

1(b) Postulate 2

At the apex of the turn the car should be going around the turn as fast as possible without losing adhesion and leaving the road. In other words using - by turning - as much of the available traction as is possible without using it all.

1(c) Assertion

The optimal driver behavior between the entrance of the turn and the apex is to release the brakes in such a way that the magnitude of the vector sum of the braking and turning forces is kept constant at that value which requires as close as is possible to but without equalling 100% of the available traction.

1(d) Corollary Hypothesis

For any given car, for every recognizable slow turn we can identify, there is an optimal de-braking curve.

“Thus, for Poker players, Game Theory bears fruit. Game Theory tells us that for every recognizable poker situation we can name, there is an optimal strategy. The strategy may be too complex for us to discern, but in theory there is one.”

- Ankeny, Nesmith: Poker Strategy: Winning with Game Theory

Game Theory also tells us that for every slow turn that we can identify, there exists an optimal de-braking strategy.

This theory claims that that strategy is to let no amount of available traction go unused. If traction goes unused then either the driver failed to either brake or turn as hard as was possible, or the entry speed was too low. Where it was the former, the brakes could have been used harder, there also existed less resultant downforce on the front wheels at that time, so there was less available traction, compounding the penalty for this error.

We have, then, that regarding Corollary 1(d), the single fastest de-braking curve simultaneously permits and requires the single fastest entry speed.

It is not a game of pushing down. It is a game of lifting up.

Release the brakes as you would approach God.

Until the apex right around 0:27.9fernando alonso onboard pole lap at magny cours 2005

When lifting your foot, do not use your foot or ankle - use the muscles in your thigh or hip, letting everything from your kneecap down hang.

Lifting your foot and turning the wheel at the same time is like rubbing your stomach and patting your head at the same time. It is not difficult but nobody gets it right the first time. You must practice it if you wish to use it.

This paper is about racing, and specifically not about driving on the street. It is, for the most part, not transferable on the street.

For example, suppose you are cruising down main street, Anytown, USA, and approaching a 4-way intersection where the speed limit is 30 in all directions. For your cruising speed to be 100-110 would be neither safe nor legal nor practical. For you to then brake quite hard down to 60 at the white line, compressing the front springs by a goodly amount, and then meter out that stored energy by staying on the brakes and exiting the turn at a crawl - 15 - because you refused to let the front bob up and 60 was too slow - this would place your street driving squarely in the realm of totally unacceptable to all other human beings.

There is one item in this paper which can be applied to street driving, and that is the comment “Release the brakes as you would approach God”. We were all taught to release the clutch smoothly, but not the brakes.

Also, many of us were taught not to brake in turns, and the reader now understands the mechanics of and good reason for this. It is not clear to me that this is always possible, given the realities of rush hour traffic behind you. But that is a different subject.

In any case, there is no conflict here. Whether you choose to brake before the turn or into it, release them with the very utmost of care and fine attention to detail.

Copyright © 1989-2025 Douglas Landau, doug.landau@protonmail.com. All Right Reserved.

Permission to copy and use for non-commercial purposes is hereby granted.

Permission for commercial purposes is granted only for internal use on company premises.

Permission to distribute is granted to all if and only if all copies are verbatim and free.

Distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited.